Poems

Carol Curran, MD Sep 20, 2022I am often reminded of poems as I go through life. Sadly, being a hospice doctor tends to bring to mind painful, troubling strophes more often than those that are hopeful, upbeat or humorous. Song lyrics (a form of poetry) like those from "Elephant," by Jason Isbell, play in my head on many a workday, when I am weary of demoralization, denial and existential dread, of patients who are too young and families that seem incapable of grace:

She said, "Andy, you crack me up"

Seagram's in a coffee cup

Sharecropper eyes, and her hair almost all gone

When she was drunk, she made cancer jokes

Made up her own doctors' notes

Surrounded by her family, I saw that she was dying alone

But I'd sing her classic country songs

And she'd get high and sing along

She don't have a voice to sing with now

We burn these joints in effigy

And cry about what we used to be

Try to ignore the elephant somehow

I buried her a thousand times, given up my place in line

But I don't give a damn about that now

There's one thing that's real clear to me

No one dies with dignity

We just try to ignore the elephant somehow

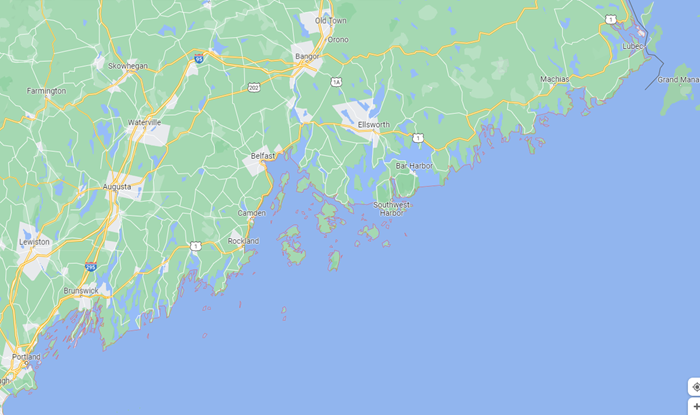

Several times a year, though, I receive the gift of time spent in Down East Maine. My sister and her husband, a sociobiologist and geneticist, respectively, moved there fifteen years ago; we visit as often as possible. The trip itself is emblematic of the difference in the pace of life between the two places. We live two hours from both New York City and Boston. Leaving home to travel to Maine I am immediately funneled into fast-moving, competitive, dense traffic. It isn't until north of Portland that the frenzy begins to abate. The straight, flat highway is suddenly bordered by giant evergreens. Traffic thins; moose crossing signs appear. East of Bangor, human presence becomes increasingly less evident, until eventually only found-item mailboxes mark driveways to unseen houses. The air clears and the coast, rocky and dramatic, appears. Finally, eight hours after setting out, a mile-long dirt road leads "home." It is quieter here than any place I have ever been.

This morning at high tide, just before launching kayaks, we watched a harbor seal following a school of fish. Paddling through the still water of the bay we spied two juvenile bald eagles, perched immobile on large boulders at the water's edge. A parent, flying overhead, warned that we were getting too close. The young ones' wings appeared underdeveloped for flying, leading us to wonder why they were both out of the nest. We'll check later today to see if they are still there, or if they have fledged enough to fly to a less exposed location.

This afternoon we'll walk the miles of trail they have created through their woods, our dogs running at least twice as far as we walk (and hopefully, for our sake, avoiding the black, muddy bogs they so enjoy). We see no large animals, but wildlife cameras have, over time, captured coyotes, bobcats, moose, hares, and snowy owls. I am reminded of Ted Kooser's "Walking by Flashlight," from Winter Morning Walks. It was written during a period of chemotherapy-induced photosensitivity, when the poet's usual walks were necessarily taken before dawn, and when the will to create, dormant for some time, was reawakening.

Walking by flashlight

at six in the morning,

my circle of light on the gravel

swinging side to side,

coyote, raccoon, field mouse, sparrow,

each watching from darkness

this man with the moon on a leash.

At the day's second high tide the ocean, returning over mud flats warmed by the sun, will be perfect for swimming. Bailey, always overjoyed to be in the water, will paddle after me. Another poem comes to mind, this time "Dharma," by Billy Collins:

The way the dog trots out the front door

every morning

without a hat or an umbrella,

without any money

or the keys to her doghouse

never fails to fill the saucer of my heart

with milky admiration.

Who provides a finer example

of a life without encumbrance—

Thoreau in his curtainless hut

with a single plate, a single spoon?

Gandhi with his staff and his holy diapers?

Off she goes into the material world

with nothing but her brown coat

and her modest blue collar,

following only her wet nose,

the twin portals of her steady breathing,

followed only by the plume of her tail.

These few days of respite and reflection renew my understanding of the words "quality of life." This was vividly articulated by the late Andrew Cadot, a Portland attorney who suffered from Parkinson's disease, whose work I discovered while here in Maine. His characterization of heaven and hell as not simply confined to the afterlife, but as states that can be found in the here and now—and which can be intentionally chosen or rejected—reinvigorates my commitment to serving patients as they face their own versions of what is, and what is to come.

If you should find me

in a hospital bed facing the wall

after a Parkinson's fall –

please do what you can

to allow me to move on, to arrive –

without tubes or ventilators

to keep me artificially alive.

With less than a decade left

before I start to lose

one by one, my marbles

and the use of my car, clubs, and computer,

my strong preference is to exit early,

rather than be charged an arm and a leg

to be resuscitated at every surly turn.

Having tasted the very best of heaven,

I will not want to stick around

to endure a private hell

without a fully functioning brain

where my face no longer smiles,

my eyes blink once for yes

twice for no, to a nurse I don't recognize.

If what is left is a poor

imitation, I pray for a pass

to seek heaven on the other shore.

I'd love to hear from you. If you have a comment, or a poem to share, please get in touch. My email is cbcurran5@gmail.com.