Out of sight out of mind: Picking up the pieces of life

Christine Merchant MSPC BSN RN CHPN Nov 2, 2021

I am asked to participate in a simulation module to understand a sensory modality relating to an illness. I am given tools to participate. I place spiky material into my shoes, put special glasses on, earphones are placed over my ears and special gloves are put on both hands. The pinky and next finger sewn together and the pointer and middle finger are sewn together leaving the thumb by itself.

I sit and wait for my turn. I am escorted into a room which appears darkened. As I look through the special glasses I notice I have no peripheral vision and looking forward is like looking through a dirty window. I am alone with no one there to help me.

A woman comes up and tells me tasks I need to do. I can’t make out what she is saying and only catch certain words. I become frustrated because I cannot hear clearly. I want to do everything right. I ask several times “what did you say” but am ignored.

I decide to figure it out. Plates, napkins and silverware are all over a table. I attempt to pick up the plates and almost drop them because of my thick fingers. Folding napkins and picking up silverware are also difficult, they are smaller than my awkward grasp. I manage but it is not perfect. After a considerable amount of time, I move on.

As I walk I start to notice a sharp stabbing sensation in my feet and shooting up my legs. It is uncomfortable at first and then becomes more annoying. This continues throughout this process.

There is a change purse and coin all over a table. I attempt to pick up the coin and can’t get my fingers to work. I can’t see the coin because the glasses are too cloudy. I have an idea of moving the coin with one hand into the palm of my other hand. When I attempt this, half the coin fall on the floor and with the bulkiness of my fingers and hands there is no way I will be able to pick it up. Frustrated I leave it there.

I see a book laying on a table and am told to read a paragraph. I pick up the book, its dark and my vision is bad. After several attempts I realize that I am not able to read. I think about how much I love to read books and it makes me sad.

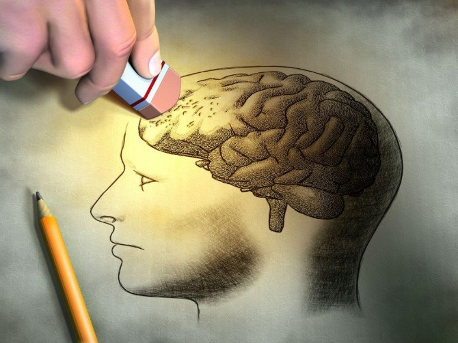

I am asked to exit the room. As I go back out into the lightened area, removing my gear I begin to reflect on my experience. I am told I just lived a brief moment in the life of a patient with dementia. Completely overwhelmed and taken over with such emotion when hearing this that tears well up in my eyes. What a powerful lesson in sensory deprivation for the simplest of tasks. I am forever humbled by this experience and see this patient population through a new lens and focus.

We have been known to label a dementia patient as behavioral in the acute care setting and then throw them in the direction of geropsych. This can sometimes lead to over medicating them to “make them behave.” Being in a foggy world where even the simplest of tasks is overwhelming can throw someone over the edge. The patient suffering from Dementia or Alzheimer’s are removed from their familiar living environment when brought into the hospital. Their people are not the same faces in this new situation and it becomes scary. We struggle with them and unfortunately use restraints when they don’t cooperate with us.

We need to work better at how to care for these patients and families who are struggling with this unforgiving disease leaving them to feel fragile, vulnerable and impotent. We need to cultivate a more peaceful environment and relieve the stress they are feeling to know that we are not the enemy.

Recently I watched the movie “The Father,” with Anthony Hopkins playing an elderly gentleman with dementia. It was sad, dark and at times made me anxious to watch at how exposed he felt as a human being. It also brought me to realize the expense of suffering on the part of the caregiver. They need to start the grieving process not at the time of passing but at the time of diagnosis to mourn the loss of their loved one as they were to the new point of slipping into the dark abyss called dementia.

This has shown me as a palliative care provider that this is whole centered care process, to focus not only on the patient but the caregiver and extended family as well. In the end we can’t take away the illness or diagnosis but we can make it more comfortable and manageable by being present and supportive.