Frequently Asked Questions

Have a question? We have an answer!

FAQs are listed in the following categories: CU Startups, Disclosing an Invention, Copyright, Patents, Trademarks, Consulting and our Healthcare Innovation & Entrepreneurship (HIE) Initiative. If you don't see your question, send us a note on our Contact Us Page.

Think like an inventor. To transition from a researcher to an inventor, focus on the commercial potential of your research. Think about how your technology can solve real-world problems and identify market trends. Connect with people in industrial R&D, such as former colleagues, friends from graduate school, and peers from conferences, to expand your network and gain insights into market needs.

Good laboratory records streamline the preparation of invention disclosures and patent applications. They also provide essential evidence to defend issued patents, especially in the U.S., where patents are granted on a "first to invent" basis.

Laboratory notebooks should include bound pages, full signatures, dates, ink entries, single-strike cross-outs, no skipped pages, initialed auxiliary materials, and preserved first samples. Digital records should be supported with written documentation.

Follow these standards:

- Use bound notebooks with pre-numbered pages.

- Sign and date every page. Record entries in ink.

- Use a single strike for cross-outs and initial them.

- Avoid skipping pages; draw a line through unused portions and initial. Initial across the edge of pasted auxiliary materials.

- Avoid thermal paper; copy data and place it in the notebook.

- Support digital records with written documentation.

- Label ideas to differentiate from actual work.

- Have records witnessed weekly by someone knowledgeable but not directly involved.

- Preserve first samples of new materials.

- Retain purchase order records for testing components.

Laboratory notebooks provide evidence to defend against patent infringement claims by documenting the conception and reduction to practice of an invention. They are crucial during legal proceedings if an issued patent is contested.

To be named an inventor, you must prove the initial conception of a novel idea and its reduction to practice. Filing for patent protection should be done with ample experimental evidence and before any public disclosure.

The two methods are maintaining detailed laboratory notebooks and filing Invention Disclosures with the Technology Transfer Office. Both provide crucial documentation to support the timing and development of an invention.

Intellectual property (IP) exists in a complex legal environment, and understanding its terminology is crucial. Overlooking contract details can lead to serious consequences, such as restrictions on publications. Always consult the University of Colorado Intellectual Property Guidebook for comprehensive IP information and seek help from CU Innovations if any contract language is unclear.

CU Startups

In most cases, startup companies seek exclusive licenses from the university to the intellectual property needed to form the core assets of the business. However, in nearly all cases, the work performed in the lab to generate the underlying IP continues well after the initial disclosure and subsequent patenting process.

Additional discoveries are often more important to the commercialization of technology than the original invention. As a result, companies seek to secure rights to follow-on improvements via an Option to Future Improvements.

Options grant a company a period of time in which to evaluate an improvement for inclusion in the company's IP asset portfolio. If the company elects to exercise the Option, this can be done for a small up-front fee and an agreement to incorporate the new technology into the company's License Agreement under the same terms and conditions as the original. If the company decides not to license the new technology, it is returned to the university for licensing elsewhere.

Two reasons. First, as discussed above, the university's contribution to a startup is usually in the form of an exclusive license to a portfolio of intellectual property assets. As a company grows, so does its need for follow-on financing. Because the university does not have the cash to participate in later-stage rounds of financing, all compensation must be negotiated in the original license with an understanding that whatever the university receives is the maximum it will ever receive. As such, the university seeks to negotiate economic terms that allow the institution to participate fairly in the upside of the company, without unduly hampering the company's ability to raise capital and execute its business plan.

Second, CU Innovations's mission is to determine the best and highest use of the technology, and then to structure an agreement that ensures the technology will be commercialized for the public benefit. Financial terms, such as Minimum Annual Payments and Sub-License Royalties, are mechanisms to discourage companies from either sitting on potentially valuable technologies (not actively marketing) or merely brokering technologies (acting as a middleman and providing little if any development and commercialization value). In most cases, CU Innovations will also include certain diligence provisions in a license agreement that further encourages the licensee to actively commercialize technology licensed from the university.

No. Stock is not received in preference to cash, but as an adjunct to both up-front license fees and future royalty streams. One way to view the university's position is to look at startups from the perspective of opportunity cost.

The University of Colorado assumes right, title, and interest to inventions and related intellectual property created by university employees. As a result of this policy, and certain obligations under the federal Bayh-Dole Act, the university has created CU Innovations and tasked it with commercializing technologies created at the university. This is typically done in one of two ways: Licensing to an existing entity or creating a start-up.

In both cases, the interests of the inventor and the university are aligned: each party seeks to maximize their return on investment. However, when CU Innovations invests intellectual property into a startup, it is deferring compensation that might be received from licensing the technology to an established company. In some cases, this deferred income, otherwise known as opportunity cost, can amount to significant sums over the period of a license. Therefore, to mitigate risk and provide the university with the opportunity to increase its potential return, licenses with equity generally do include cash payments:

Up-front license fees (where applicable and imposing a low cash burden)

Minimum annual and/or milestone payments

Royalties on net sales

Sublicense royalties

Equity is the currency most readily available to startup companies. Since startups usually begin as a concept, they need time to assemble the resources necessary to maximize chances for success. Often, CU Innovations and the faculty inventor wishing to create a startup, are in a kind of "chicken and egg" situation. The startup needs a secure commitment from the university that it has, or will soon obtain, full and exclusive rights to market a particular technology and the University seeks to grant licenses only to entities it believes have the capability of rapidly, and profitably, commercializing the technology.

To bridge this gap, CU Innovations works to create conditions that are ripe for investment in the startup. Financially, this means the university acts as a founder of the company, understanding that startups typically have little cash and no revenues. As a founder, the university typically accepts non-marketable stock in lieu of cash as compensation. Founders stock is viewed as a reasonable business solution to enhance the overall financial package for the technology acceptable to the company and its future investors, while providing an opportunity for the university to participate in the upside of the company.

There are several reasons why CU Innovations works to create startups from university inventions:

Startups translate academic inventions into commercial goods and services that benefit the public. This is consistent with the mission of universities

A track record of successful startups helps during discussions about recruitment and retention of high-quality faculty.

Startups are an engine for local economic development and job creation, and success in this area demonstrates the value of university research to the broader community.

Startups are sometimes the only alternative. In some cases, individual technologies cannot be licensed piecemeal. A great deal of work needs to be done to identify, package, and present a basket of technologies that cohesively offer a commercialization opportunity.

Startups make money - for the inventor, the university, and the business and investment community.

About 5-10% of inventions meet the criteria necessary to become startup companies. At CU, this translates to 5-10 startups per year.

Patents

The America Invents Act (AIA) shifted the US patent system from first-to-invent to first-to-file. Now, the person who first files a patent application is recognized as the inventor and owner, regardless of who invented it first. Maintaining meticulous records before AIA could have affected inventorship claims. However, good record keeping remains crucial. This is vital for CU Innovations to accurately assign inventorship and for collaborative inventions, ensuring each contributor's role is clear.

It is important to note that there are exceptions to the first-to-file rule. Therefore, if you think you have an invention, you are encouraged to contact CU Innovations.

Sponsoring agencies sometimes require the university to disclose inventions that arise from work they fund. If the research that led to your invention was sponsored, give details and a reference to the contract or grant agreement in the Invention Disclosure Form.

Publishing and applying for patent protection are not mutually exclusive: they can be done simultaneously under the proper circumstances. U.S. patent laws allow one to apply for a patent no later than one year after a public disclosure, such as a published paper, a widely available abstract, or an offer of public sale. However, the moment a public disclosure or publication is made, rights to foreign patents are lost unless a U.S. filing has been made within the preceding 12 months. Foreign protection is important to many international licensees, so inventors are urged to use discretion, take advantage of Confidential Disclosure Agreements available from CU Innovations, and file invention disclosures with the university well in advance (ideally one month or more) of presentations or publications.

Inventions include new processes, products, apparatus, compositions of matter, living organisms, and/or improvements to existing technology in those categories. Abstract ideas, principles, and phenomena of nature cannot be patented.

Process: A method of producing a useful result; it can be an improvement on existing systems, a combination of old systems in a novel manner, or a new use of a known process.

Machine: An apparatus from a simple device to a complicated combination of many parts that performs a function and produces a definite result or effect.

Manufactured product: An article that is produced and has a usefulness.

Compositions of matter: Chemical compounds, and mixtures such as drugs and, more recently, living matter.

In the United States, patentability is determined by novelty, utility, and nonobviousness.

Novelty: An invention is "novel" if nothing identical previously existed. How does your invention differ from what already exists? In what ways might it not be unique?

Utility: An invention is useful if it produces an effect, if the effect is the one claimed, and if the effect is desirable to society, at least in principle. Who might find your invention useful, and why?

Nonobviousness: Nonobviousness measures the degree to which an invention differs from the totality of previous knowledge, and the degree to which an invention could not have been anticipated from that knowledge. At the time it was conceived, why might your invention not have been obvious to people reasonably skilled in the field? Are there ways in which it might be an evolutionary step? What is the difference between the proposed invention and what has previously existed?

An inventor is the one who first conceives of an invention, in detail, and with enough specificity that one skilled in the field could construct and practice the invention. Those who translate the concept into practice are not considered co-inventors unless they add to the original concept of the invention. With the agreement of the inventor(s), however, they may share in financial benefits of the invention.

A patent is a 20-year monopoly that allows the patent owner to prevent others from making, using, or selling the patented invention without permission. In return for the monopoly, the inventor must make known the details of the invention so that others can seek improvements or new uses. The inventor gains by exclusive access to the invention, and society gains by using the detailed description of the invention to further advance technology.

Copyright

Copyright is a form of protection grounded in the U.S. Constitution and granted by law for original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Copyright covers both published and unpublished works.

The subject matter of copyright is original works of authorship, including literary and musical works, engineering designs, software source code, graphic works, sound recordings, and works of art. Software programs as well as mask works for computer chips can sometimes be protected by patents in addition to copyrights.

Copyright applies only to an author's original expression, not ideas, since ideas belong to the public and may not be monopolized. The idea-expression distinction explains why an original text on plane geometry may be copyrighted, though earlier copyrighted works presented identical ideas. Similarly, anyone can freely use data from a copyrighted book listing melting points of chemical compounds, since empirical data are considered ideas. Unauthorized photocopying of pages from the same book might be copyright infringement, however, because it appropriates the author's selection and organization of data, and the layout of pages and headings, all of which might be original expression.

See Circular 1, Copyright Basics, section "What Works Are Protected."

To be copyrighted, material must be original and fixed in a tangible medium of expression.

Unlike patented inventions, there is no requirement that a copyrighted work be novel in the sense that nothing identical previously existed. The criterion of originality is met if a work is the author's own, not copied from another source.

Prior to 1978, authors were required to adhere to certain formalities (register works with the U.S. Copyright Office, use © notice on works) to obtain full protection, but since a revised federal statute became effective on Jan. 1, 1978, copyright now exists in an original work of authorship as soon as it is fixed in a tangible medium of expression such as a manuscript, audio tape, or computer file. For works created after 1978, former statutory requirements such as copyright registration and use of the copyright mark, ©, are now useful mainly as prerequisites to infringement proceedings to enforce copyright or recover damages for unauthorized use.

In the case of software, copyrights exist even if the copyright notice is not included in the source code. An author may intend to commit the source code to the public domain by leaving off the copyright notice, but they have not granted any rights to others to modify and copy their code. It is a good practice to search for a license statement or to ask the author’s permission before including their code in a new work.

Ownership of copyrights in works written as part of university responsibilities depends on the nature of the copyrighted work. In keeping with academic tradition, copyrights in textbooks or other works of a primarily pedagogical or scholarly nature vest with the faculty author, as governed by CU's Policy on Intellectual Property that is Educational Material. Copyrights in faculty works of a commercial nature, such as training materials for nurse practitioners, would belong to the university, at least in part, if the works were developed using university resources or developed under a university-managed Sponsored Research Program.

Copyrights in software developed by university employees are owned by the university, as governed by CU's Intellectual Property Policy on Discoveries and Patents for their Protection and Commercialization. Royalty revenue from university licensing of copyrights is shared with faculty authors of the work and their research groups and administrative units.

Copyright notice can be added to a work as soon as it is written. Formal copyright registration is not necessary. Add the notice below to your copyrighted materials.

Proper copyright notice for University of Colorado software: Copyright <Year> Regents of the University of Colorado. All rights reserved.

For software, it can be included in source code files and/or a separate license text file and/or documentation. It is recommended that the copyright also be included on the website. CU Innovations can provide advice on copyright and licensing of software.

To begin this process, download the Copyright Submission Form. Return the form to CU Innovations located at the Anschutz Health Sciences Building, 1890 N. Revere. Ct., Suite 6202, Aurora, CO 80045, or email the completed form to your CU Innovations case manager or [email protected].

For works with commercial applications (such as software), CU Innovations can assist with the copyright registration process, help identify potential licensees, and negotiate licenses.

Although copyright allows authors to prevent unauthorized use of an original work, there are exceptions. Limited copying for the purpose of criticism, comment, teaching, scholarship or research is usually not infringement of a copyright. For more information on fair use, see the CU Health Sciences Library website on the subject.

All members of the project team should agree on common goals for the software and the roles of group members. As the developer community grows, it may beyond the research group, or even the university. It is very important that the copyrights are managed so that the project team has the rights to distribute the project to future collaborators and users. We recommend asking all contributors to agree to the Contributor License Agreement which is based on the Apache Software Foundation's agreement.

University software is subject to the royalty distribution formula in CU's Policy on Discoveries and Patents. If a software project grows to include many CU staff and students over time, each individual may be entitled to a portion of the 25% inventor's share of royalties. Some groups choose to direct the inventors' share into a pool of funds to support the project itself. It is necessary for all CU contributors to sign a Project Participation Agreement to make that possible.

How do I copyright and license my creative/scholarly/pedagogical works?

For information on copyrighting your creative/scholarly/pedagogical works, see the CU-Health Sciences Library website on the subject.

Trademarks

When an allegation of trademark infringement arises, the case can be tried in federal court if the contested mark is registered, or in state court if not. In federal court, the registered owner is presumed to have the right of ownership and to exclude others from use of the mark. In the absence of a federally registered trademark, state courts will examine factors such as how long each merchant has used the contested mark, how distinctive the mark is, whether the merchants maintained control of their marks, and whether they do business through similar channels of trade and in overlapping geographical regions.

State courts will particularly focus on public policy interests, and estimate the likelihood of confusion by the average consumer. For example, although a law firm database had for many years done business under the name "Lexis," an automaker was subsequently permitted to use the name "Lexus." The court reasoned that, as lawyers, Lexis customers are presumably sophisticated enough to avoid confusion, and that buyers of a luxury automobile are unlikely to be surprised when they do not receive a database report.

In order to receive federal protection for a trademark, merchants must apply for federal registration at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO). This is the broadest trademark protection available as it is nationwide protection. The process to obtain a federal registration takes approximately nine months. Once federal registration is granted, notification to the public and other merchants that the trademark is federally registered may be accomplished with the symbol ®. If no other merchants file objections to the registration within five years, the applicant may file an affidavit with the PTO claiming continued and uninterrupted use and then the registration would be incontestable. Federal trademark registrations are renewed every ten years, as long as the trademark is still in use.

To receive protection under state law and within the regions where a company does regular business, a merchant need only use a mark consistently and maintain control of its use. Notification to the public and other merchants that the symbol or phrase is being used as a trademark may be accomplished with the superscript symbol TM. The price for a merchant's failure to maintain control of a mark is that words or phrases that were once trademarks may fall into the public domain, at which point they are no longer protected under the law. "Aspirin" is an example of such a lost trademark. A State Registration may be obtained for a trademark through the Secretary of State’s Office for a nominal fee.

Protection is proportional to distinctiveness. Whether a trademark is a symbol, word or a phrase, it should be easy to recognize if it is to serve as a quick identifier. Depending on the likely ease of recognition, courts sometimes classify trademarks into three loosely defined categories:

- Distinctive trademarks: Made of a coined word or specially designed symbol, these trademarks are unique and are afforded the strongest protection under the law. Examples of distinctive trademarks are "Xerox," the silhouette of a buffalo overlaid with the interlocking letters C and U, and the musical notes G-E-C of the NBC network motto.

- Suggestive trademarks: These trademarks describe a product but also hint at an origin or characteristic, typically with an unusual twist or combination of words. Examples in this fuzzy category might be "Ivory Soap," "Mister Donut," and "Wheat Thins."

- Descriptive trademarks: This category is the least distinctive in that they are composed of common words used in a common way. To receive any protection, these merely descriptive trademarks must have acquired a secondary meaning, for example through the public's long association of the phrase with a particular merchant. "Park & Fly," "Builder's Warehouse," and "The Country's Best Yogurt," are examples.

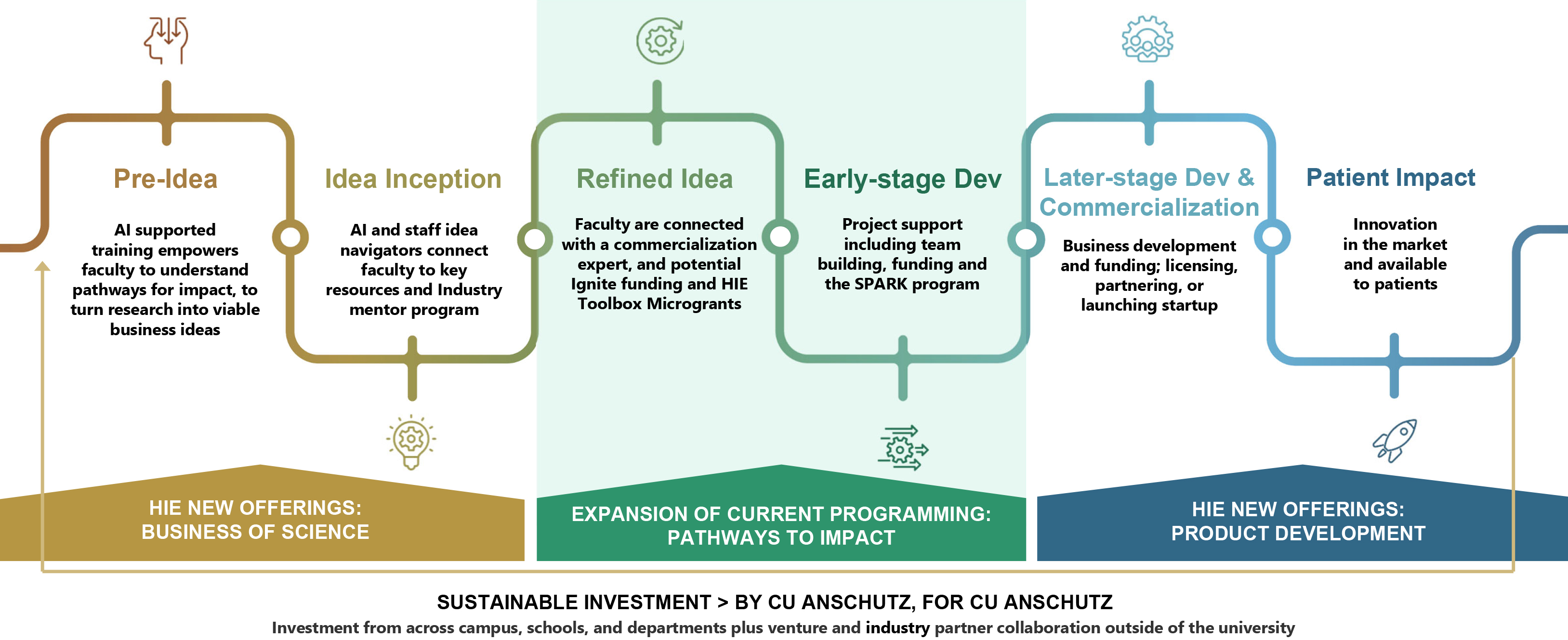

HIE provides concierge style support to shareholder departments across CU Anschutz. There are several new offerings:

- HIE creates a single, coordinated front door for healthcare innovation at CU Anschutz through several easily accessible touch points: new HIE Impact Champions embedded in each shareholder department and newly hired Staff Idea Navigators to field inquires across the entire campus. These resources enable more rapid assessment of ideas to help innovators translate discoveries into viable market options. This allows CU Innovations to engage earlier in the lifecycle with more early-stage idea innovators and provide clarity and support. This addresses a direct need expressed from faculty and campus interviews regarding confusion on how to get involved or who to go to in order to get started with innovations or exploring an idea. HIE Impact Champions and Staff Idea Navigators help embed innovation as a core tenant of research across departments, not as separate activity.

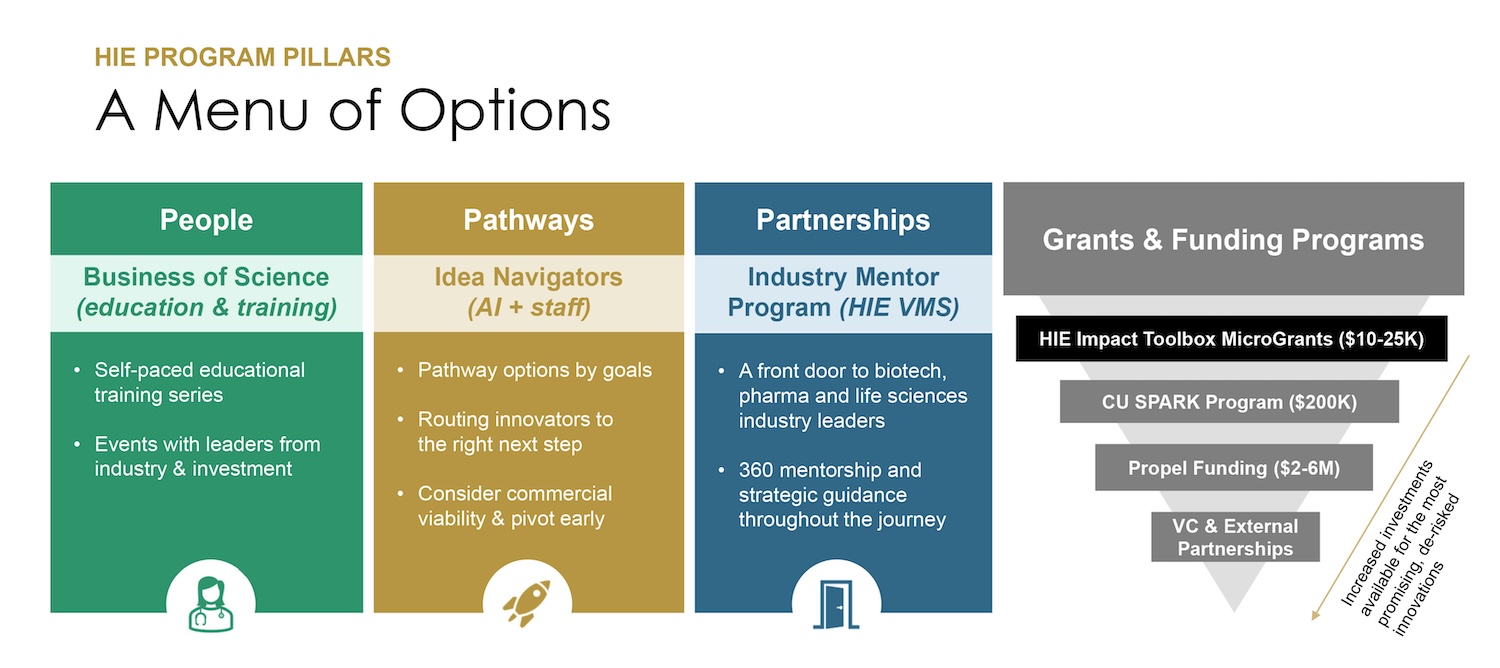

- HIE is implementing a formal HIE Venture Mentor Service, with Entrepreneurs in Residence (EIRs), expanding on the current commercialization expert connection that happens post idea refinement and allowing access to mentors across all business, legal, marketing and other specialty areas to help guide campus innovators. The team is creating this program licensed from MIT’s Venture Mentoring Service model and integrating lessons learned from our SPARK Colorado program at CU Anschutz. This network expands our outreach and engagement of mentors to create a sustainable and modern mentoring program.

- HIE is strategically filling the valley of death gap in funding, which impacts most innovators, by creating new business development and grant funding opportunities to support later-stage development. The goal is to strategically increase investments available for the most promising, de-risked innovations across campus.

- HIE expands support and awareness for all commercialization pathways (startup, licensing, consulting, partnerships, etc.) to support more faculty, students and staff in finding the right path to reach patients while considering their career goals and risk appetite.

- HIE’s mission is to invest in people, not just one-off technologies. By investing in new education programing via the Business of Science training series and expanding mentorship and external industry connections, innovators learn the importance of pivoting and understand why some early ideas may not succeed. By focusing on innovators, HIE supports a sustainable, iterative approach to translating research discoveries into real-world opportunities.

- Additionally, HIE connects into the Presidents Innovation & Entrepreneurship Initiative and long-term goals for CU at large by raising the visibility of innovations at CU Anschutz through strategic communication, marketing and media, as well as policy advocacy.

Please see the graphic below for a general “Innovators Journey” and new HIE offerings in yellow.

Yes, SPARK will continue annually and remains a core funding mechanism for innovators at CU. Through HIE, we are expanding funding opportunities available for later-stage developments, including through new grant opportunities and VCs and external partnerships. See the menu below.

HIE kicked off in fall 2025 and has several opportunities already available for campus innovators including:

The Business of Science training series, which includes live and on-demand webinars as well as in-person events connecting our innovators with external industry and investors.

HIE Impact Champions have been nominated and selected in each shareholder department and will continue to be announced as new shareholders come on board. Please see the list of Champions here. Campus innovators can go to their department Champions as a first access point in navigating innovations to support and explore an idea.

The team has started building Staff Idea Navigators, including the hiring of former Fellow, Lily Elizabeth Feldman, who will serve as support in assessing pre-idea questions and concepts and helping innovators find viable market solutions to pursue.

The team is building an on-demand, AI-powered educational program that will allow campus innovators to earn a Certificate in the “Business of Science.” The program will run at your own pace, customized to your specific interests and level of expertise. The curriculum has been created and the team is working with partner, Amplifire, to launch in early 2026.

In January 2026, we’ll kick off the pilot of our new HIE Venture Mentoring Service program, which we’ve adapted from MIT’s Venture Mentoring Service. We expect to roll this program out more broadly in the summer of 2026.

- Save the date for our HIE Impact in-person event on April 21, 2026. Sign up here for early notifications and stay tuned for RSVP, agenda detail, guest speakers, and more.

- The Business of Science educational training series is open and free to all CU campus innovators – faculty, students or staff.

- In the meantime, to stay engaged and apply for new opportunities, sign up for our HIE Impact email listserv here, follow CU Innovations on LinkedIn and YouTube, and check the CU Innovations HIE webpage here.

- You can also check in with your department HIE Impact Champion on the latest – see Champions here.

- You can always directly reach the team at: [email protected]

- Our team is currently working on developing a monthly newsletter including new opportunities, funding, programming, events, innovator highlights and more. Stay tuned this Winter.

The ultimate success metric for HIE is patient impact – if we are able to get a new innovation into the market to positively impact the lives of patients.

Other success metrics include:

- Expanding the innovations mentor pool

- Successfully launching the HIE Impact Champions program in each shareholder department

- Awarding a minimum of $2M in funding across programs

- Engaging 250+ innovators across campus

- Creating new seminars, events and trainings to educate on the Business of Science

- Recognizing HIE Impact innovators in public-facing video series

HIE is generously funded by Chancellor Elliman, Dean Sampson and leaders across the School Medicine and School of Pharmacy. See a complete list of our sponsors here.

Use this form to let us know what you’re interested in and we’ll make sure to connect you with the right person.

Yes! Please use this form to reach out to us, and we’ll be in touch.

HIE Impact Champions are faculty leaders at CU Anschutz, nominated by the department chairs of the HIE Initiative’s founding shareholders. Champions share knowledge about the initiative within their professional networks and serve as points of contact for questions or engagement. See and connect with your champion here.

Consulting engagements accepted may or may not be directly related to the University of Colorado's mission. Examples of consulting services may be serving on a for-profit corporation board as a medical advisor, performing a series of seminars or conferences, serving as a newsletter editor for a medical society and other like activities.

Existing agreements stay with CU Medicine through June 30, 2026. If billing continues beyond June 30, 2026, the agreement with get amended and transferred to Innovations.

Existing rates will remain in place. If you have a legacy CU Medicine agreement that we are amending and transferring, we will keep the CU Medicine rates.

Any new agreements, including amendments, renewals, or new scopes of work, after January 5, 2026 will be submitted to Innovations.

We are already working toward updating master agreements with key partners to ensure new scopes of work can be completed under Innovations as quickly as possible in 2026. If you have an ongoing agreement with a company that you think might need to be transferred to Innovations, please reach out to us.

Yes! When submitting a new agreement, departments can select our template in Ironclad and it will auto-populate based on the form responses. We will then route that to the counterparty.

- If you have a question about the transition from CU Medicine that is not answered on this page, please reach out to Jordan Ross.

- If you are a faculty member and have a question about a contract you have submitted or completed with us, please reach out to your department administrator.

- If you have a question about billing or finance, please reach out to Brad Harrison.

- If you have questions about how to use the Ironclad software, please reference the Ironclad User Guide linked above.

- You can also find the list of program leaders here.

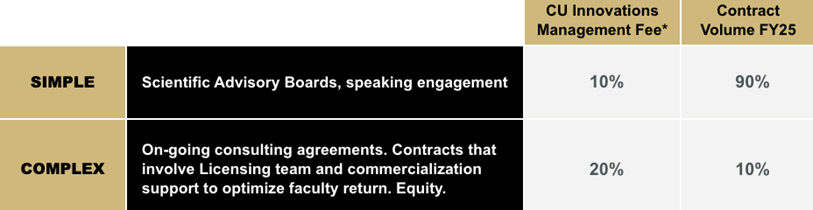

We look forward to optimizing revenue options through this change. Simple contracts, including but not limited to scientific advisory boards and speaking engagements, will incur a 10% management fee. Complex or large-scope contracts — including but not limited to ongoing consulting agreements, contracts that involve licensing and commercialization support to optimize faculty return, or include equity — will incur a 20% management fee. Each agreement is nuanced, but we expect only ~10% of all consulting contracts to fall into this category.

Innovations will be trialing this new structure for one-year and it is subject to change.

Note: Agreements filed on January 5th or later through the new process (with Innovations and Ironclad) will be subject to these new rates. For existing agreements or those, current rates will be honored and will not change.

Innovations brings deep expertise in managing intellectual property, and this transition will provide greater visibility and alignment with existing protections. Faculty can continue to expect safeguards for their work, with the added benefit of Innovations’ dedicated focus in this area.

All income, fees, retainers, or other compensation received for professional services shall include but are not limited to cash, checks, deferred compensation, warrants, phantom stock, stock option plans or arrangements and any other compensation or benefit plans or arrangements.

Consulting revenue is defined as non-clinical revenue performed for non-affiliated entities such as academic and/or medical societies, pharmaceutical or medical instrument/device for-profit corporations and the like.

In August 2025, Members approved a resolution that faculty will directly contract and bill for any Medical or Legal work they perform, instead of going through CU Medicine. Examples of Medical/Legal services include: testimony/Expert witness at a trial; record review in preparation for a legal case; a report or letter preparation to support a legal case; deposition; and more. For more information about this change, including timelines, FAQs and examples, please visit this page.

With this upcoming change, administrators can expect an initial response to submitted requests within 48 business hours. At that point, our team will indicate whether the agreement falls into the Simple or Complex fee category noted above and outline the next steps in the process. For subsequent communication, including negotiations, we aim to respond within 48 business hours.

Yes! Ironclad will be integrated with university SSO, so you can log in using your existing university credentials — no separate username or password required.

The experience to providers will be largely unchanged, though, all facets of the contracting process will be moving from CU Medicine to Innovations including the billing workflow after agreements are executed.

Innovations

CU Anschutz

Anschutz Health Sciences Building

1890 N Revere Ct

Suite 6202

Mail Stop F411

Aurora, CO 80045

303-724-3720

CMS Login